Fraud usually gets talked about in numbers like how much money was stolen, how many people were affected, how many cases got filed. But behind every one of those numbers is a person who’s been blindsided, manipulated, or left trying to rebuild trust in others and in themselves. This episode shifts the focus back to those human stories and the fight to protect them. My guest, Freddie Massimi, has spent more than a decade helping scam victims find both financial and emotional recovery, bringing empathy and understanding to a field that too often feels cold and procedural.

As a certified financial crimes investigator and program manager at The Knoble, Freddie has made it his mission to bridge the gap between institutions and individuals. He shares the heartbreaking and hopeful moments that define his work including one phone call that saved a life. Along with how that experience changed the way he thinks about what true fraud prevention really means.

Freddie also opens up about The Knoble’s Post-Scam Victimization Guide, a collaborative, trauma-informed resource designed to help victims regain control of their lives and prevent re-victimization. From crypto scams to romance cons, he explains how these schemes keep evolving, why empathy is still one of the best tools we have, and how every fraud fighter can make a difference simply by listening and responding with humanity.

“The Knoble’s Post-Scam Victimization Guide isn’t just another awareness pamphlet. It’s actionable and trauma-informed, a real playbook for recovery.” - Freddy Massimi Share on XShow Notes:

- [00:40] Freddie shares his background as a certified financial crimes investigator and program manager at The Knoble.

- [01:40] A look back at Freddie’s early path into criminal justice and how empathy shaped his fraud-fighting approach.

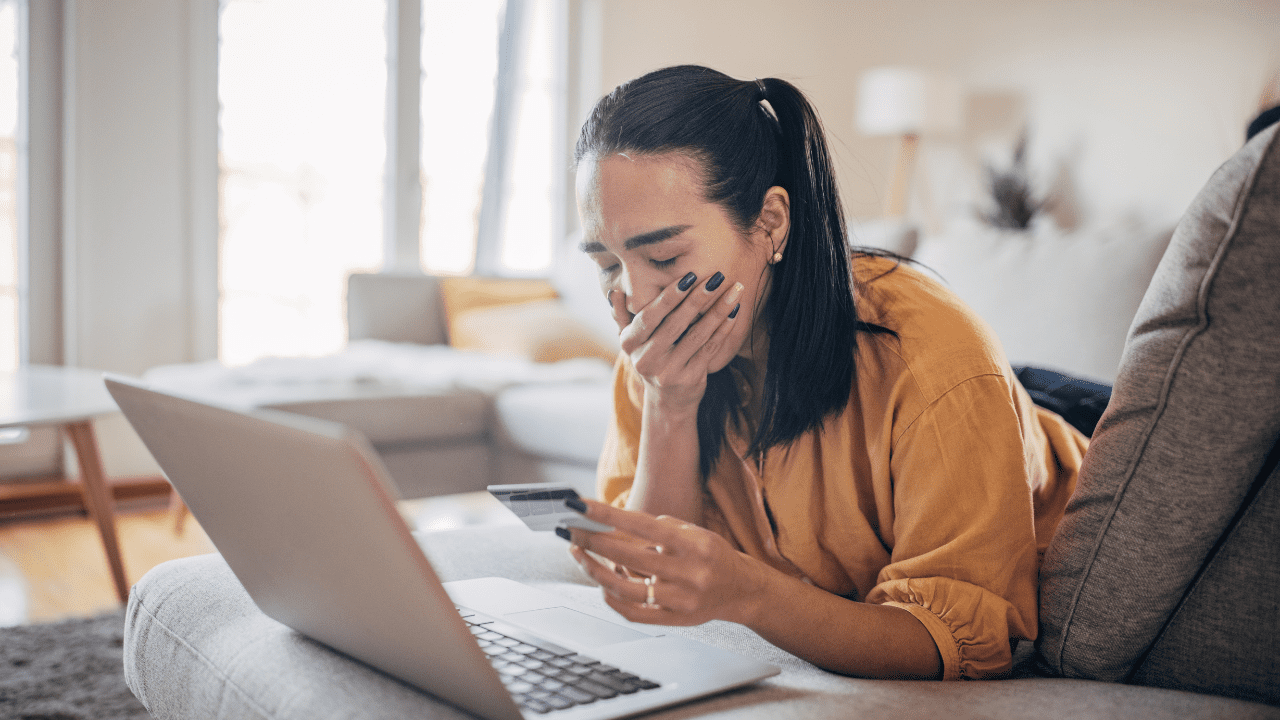

- [03:07] The story of a Tennessee widow who lost $300,000 in a pig-butchering crypto scam.

- [04:30] Freddie’s emotional account of saving a victim’s life and how it reframed his mission to protect others.

- [07:42] The rise of collaborative fraud-fighter networks and Freddie’s work leading The Knoble’s post-scam initiatives.

- [08:11] How The Knoble unites financial institutions, law enforcement, and NGOs to address “human crime.”

- [08:58] Development of the Post-Scam Victimization Guide, a trauma-informed resource for banks and fraud teams.

- [10:39] How financial crime has evolved from simple check scams to complex digital exploitation and trafficking.

- [13:01] The need for faster, more transparent information sharing between banks and law enforcement.

- [14:04] What makes the Post-Scam Guide different including actionable steps, empathy-driven language, and real-world tools.

- [15:00] Sextortion cases, Gavin’s Law, and how shame and silence compound the harm.

- [18:30] Practical tools in the guide, including hotline numbers, QR codes, and scripts for supporting victims.

- [20:20] How to talk to romance scam victims with compassion including using questions that spark reality checks, not judgment.

- [22:00] Why shame keeps scams underreported and how trauma-informed communication changes outcomes.

- [23:19] The role of technology in scams: remote access, malware, and how scammers exploit smartphones and computers.

- [24:36] Shoutout to Kitboga for his cybersecurity tools and awareness campaigns against scam call centers.

- [25:22] Why elderly victims remain the most vulnerable and how education can empower prevention.

- [27:24] The double victimization cycle like when scammers return pretending to recover lost money.

- [30:00] Freddie’s real-world example of helping a victim secure their accounts and recover identity.

- [32:50] How banks can adjust fraud detection systems to catch hidden patterns of exploitation.

- [34:30] Spotting red flags in gift card purchases and why speaking up can literally save lives.

- [36:31] Freddie’s advice for anyone who suspects they’re being scammed: stop all contact and secure your accounts.

- [37:06] The importance of documenting everything and reporting through IC3.gov and law enforcement.

- [38:30] Emotional recovery and community support are just as vital as financial recovery.

- [41:00] The biggest mistake victims make after being scammed is staying silent out of shame or fear.

- [41:40] Freddie’s story about protecting his own grandmother from IRS and WhatsApp scams.

- [43:00] Common text-message scams and why you should never reply, even with “wrong number.”

- [44:48] How to access The Knoble’s free, vetted Post-Scam Victimization Guide.

- [45:30] Where to connect with Freddie and The Knoble’s wider fraud-fighter network.

Thanks for joining us on Easy Prey. Be sure to subscribe to our podcast on iTunes and leave a nice review.

Links and Resources:

- Podcast Web Page

- Facebook Page

- whatismyipaddress.com

- Easy Prey on Instagram

- Easy Prey on Twitter

- Easy Prey on LinkedIn

- Easy Prey on YouTube

- Easy Prey on Pinterest

- The Knoble

- Freddy Massimi – LinkedIn

Transcript:

Ben, thank you so much for coming on the podcast today.

I'm happy to be here, Chris.

Can you give myself and the audience a little bit of background about who you are and what you do?

Sure. I grew up in Kentucky in a city called Bowling Green, Kentucky. I spent my early years wanting to be a police officer. I started as a police explorer back in the 90s, if you're familiar with that concept. While I was definitely underage, I got to run around with the cops and see what all they did, and I absolutely fell in love with it.

After graduation, I actually went on to college in Ohio. I studied criminology and sociology at Cedarville University, a small Christian college there. I worked security while I was there all four years. I got married my senior year, I came back home. We're both from that area. I went into law enforcement in my hometown. I did that for about six years.

I absolutely loved it. I got the honor to do crime scene investigations. They sent me to the National Forensic Academy for 10 weeks and we blew up cars. We took pictures, set things on fire. We got to go to the Body Farm that's well known at the University of Tennessee and all those fun things. I came back again doing crime scene work and policing. I felt a tug that there was a little bit more to what I could offer the field as a whole. I wanted to help people do a really good job being really good police officers.

My dad is actually in education, so I was familiar with that concept. I went back to school to the University of Louisville online for a master's program, and then I eventually got in a full-time position there going back to get my PhD, which is quite a slog to get through that. While I was doing that, I started teaching also at the college level. We moved to Louisville, Kentucky. I began doing research, began going back to school, began teaching, and all these changes at once. That led me to where I am today teaching out of the university.

Nice. Was there something specific that drew you to law enforcement? Some people are just like, “Oh, I really want to do this.” Some people are just like, “No, it's just always been in my blood.”

It sounds so cheap to say because everyone says it, but I really wanted to help people. I enjoy that aspect of it. I think I enjoyed the fact that it was something different. There was always a level you could get better at. No matter how well a case went or whether you could get a confession out of somebody, you could always do better. I think part of what I really enjoyed was analyzing how things went. Could that help me to do a better job the next time around?

I'll confess, one of my favorite things about policing after I got into it was what I jokingly call trespassing. Police officers get to go some really wild places. Burglar alarms at a restaurant, you get to see the kitchen in the back, and houses that are under construction or places that are closed off of the public where somebody's run into. I actually enjoyed seeing behind the scenes of what you normally see in your average life. I actually found that fun too.

As a kid, I did some of those things on the opposite side of the equation. Where can we go and not quite get into trouble, but go where we're probably not supposed to be as kids?

Absolutely. The differences in policing, I was paid to go to those places. It was a lot of fun, so I thoroughly enjoyed it.

It was funny that you mentioned crime scene investigation. I was the first and subsequently the last person to do a ride along with a crime scene investigator in the town that I grew up in. It was jokingly the one day with no crime. Every call that was happening, it's like, “Oh, hey, great. I'll be able to take you here. We’ll do fingerprints.” On the way, it's like, “Oh, nope, not there. OK, let's go here. Oh, nope, not there. Oh, let's go here. Oh, nope, not there.” The whole day, there was just nothing for a crime scene investigator to do. They said, “That was a horrific waste of his time. We won't be doing that again.”

It could have always gone the other direction, and it could have been more than you were ready to handle.

That's true. I'm OK with the fact that it was interesting, because it could have been interesting in a really bad way. Let's go on and talk about it. What is the specialty that you are researching?

I'm a professor of Criminal Justice at Middle Tennessee State University. Been here since 2016. What I found is I actually really enjoy doing research in addition to teaching. I've gotten into some very interesting areas, a lot of it is influenced by my background in policing and my desire and interest in actually preventing crime rather than trying to understand the nuances and psychology of why people commit crime. I'm really curious, how do we prevent it from actually happening? That has led to some interesting areas of study.

Two of the most popular are my research that I've done on people who steal metal, copper, air conditioners, catalytic converters, anything like that. The secondary area that I've started the last couple of years since 2020 is porch piracy and package theft. I've looked at both of those pretty extensively.

Cool. Let's start with the metal theft. I know out here in LA, we have a bridge that was either renovated or built, I think, in 2022. I think within a week of them opening the bridge to the public, someone yanked out all the copper or electrical wiring on the entire bridge. You and I had a discussion earlier as to whether or not they actually put it back or not, and it's been stolen again. We're not sure, but we know it doesn't work currently.

This is really a shame. One of the hidden parts of metal theft is the damage that it does and the expense to put it back. The value of the copper that they may have yanked out of that bridge could be high, maybe a couple thousand dollars at a scrap yard or something, but the cost to put it back in when you consider the man hours, the tools, and things that are necessary. I interviewed offenders who would go into a house and they would rip electrical wiring out of drywall, or they would go into a new apartment complex and bend the copper pipes off where it comes out of the cement. Now you’ve got to jackhammer the cement back up and recouple it. The expense to actually replace these items far exceeds the value of the metal that's actually stolen.

Over the years, a lot of states have really gotten wise to this and started passing some legislation to have enhanced penalties, considering the amount of damage that's done, but it doesn't seem like those have really worked. It is a very complex issue, and it has a lot of ripple effects beyond just the copper that's stolen. Your case in point, you can't enjoy the bridge or the beauty of it because the copper's been taken.

I know California, I think just this week, passed some additional laws concerning the metal recyclers that they now, at least in California, have to have driver's licenses of the people they have to report, maintain lists of the quantities and the type of materials that were brought in, and all that stuff. If they don't, then they are subject to criminal prosecution.

Yeah. It's a real interesting question of whether these things work or not. When I was doing what I call field work, I actually went out, talked with people, walked around with people who were collecting metal legally, but also got to go hang out with some of the folks who were stealing it. What I found was that it really wasn't a simple solution.

For instance, almost everybody that I interviewed for my book on the topic had been involved in an industry where they understood the value of metal and where it was at. They were roofers, plumbers, they worked in an auto mechanic shop, something like that. What I found is that a lot of them had a letter from a former employer that said, “Oh, this is Joe. He takes the scrap into the week to the scrap yard. He works for me.” A lot of people are transient employees, so a scrap yard may have had verification that a person is selling what they presume to be legal scrap from an air conditioner repair person, but they maybe have not been employed in that person for six months to a year. There's a lot of things that go on there.

Another case I talked with, a lady was gathering some material to recycle legally after her house was being renovated. Quite literally, the local gang arrived and said, “No, we're going to take this and we're going to recycle it.” They called somebody who pulled up with portable scales. Already had a lot of other metal, maybe legally acquired, maybe not, added it to the list, they paid cash, and drove away. We're even using fencing if you'll get the parts there to try and sell our metal to scrap yards. While some of these efforts may be helpful, it could be very easy to bypass this by selling it to a third party or just getting a letter from an employer and then quitting that job. It's really hard to know that we can fix this at the scrapyard.

Metal theft just seems like an odd thing to steal. Is it the thing that I'm not stealing a person's wallet from them, I'm avoiding the physical contact risk associated with it? It just seems like a really high-risk, low-reward crime.

Yeah, it is interesting and different. There were quite a few people who mentioned to me when I was interviewing them, including some of the thieves who were like, “Oh, this is a help to the environment. I'm recycling.” Which was humorous. I'll tell you, it has historically been going on for such a long time. For instance, I had the opportunity to go to Greece this summer. I'm walking around Greece and admiring all the beauty that's there.

One of the guides is telling us that inside of each of the columns was a piece of metal in the center that held it together. What would happen is people would go and they'd chip out in between the two columns to the side. They pull this metal out so they could recycle it thousands of years ago. Eventually, the column would fall over. This is why a lot of the columns have fallen over in these ancient places. They were stealing metal back at the very beginning.

There's always been an attraction to it. That's why I mentioned that a lot of people have experience in the field working with metal because you have to understand the value of it, understand where it's at, and understand what to do with it. Or it isn't intuitive like, “What would I do with this piece of copper?” There has to be some background or training from another thief or something like that that says, “This is how this works.” What we see over time is that the value of copper and in other metals indicates exactly how much theft is going to happen.

I recently did a study on catalytic converters. That's the part of your exhaust system in your car that reduces toxins and pollutions. It has been mandated since the 70s in every car. It's part of your exhaust, so you can crawl underneath the car. You can take [inaudible 00:11:59] or even just a wire cutter. You can cut it out in a matter of seconds. It's about a foot or two long, depending upon the car. It's got rhodium, platinum, and peridium in there, which are very valuable.

What we find is whether it's those semi-precious or precious metals per copper, as the price increases, so does the theft in a very predictable way. What we're seeing right now is some all-time high with copper value. Copper is now valued higher than it was even around 2008, 2013, and 2012. We're seeing a resurgence of the theft. I think anytime you see that value go up, you're going to see it increasing the theft.

With the people stealing copper wire from street lights and things like that and construction sites, is it usually people that do have a background as an electrician or has somebody just told them, “Here's how to do it so you don't kill yourself while you're stealing the wire”?

Yeah. That's a great question. When you're stealing what we call energized lines, that's a risky business. I didn't have enough people stealing wire in particular to really answer that question. Just like I said, generally speaking, there's some familiarity, or like you pointed out, it could be somebody who knows about it who taught somebody who taught somebody. It's not rocket science, if you will, to go in and yank cables out. It is dangerous to do it when it's electrified certainly, but there are ways to counteract that as well.

Is this just more of an issue of city planners and companies that design streetlights just need to build these things differently? You're usually trying to build it for ease of access. If something breaks, you want to be able to get in there. Are there simple things that they could do, or is it more complex things that they have to do to make this infrastructure less vulnerable?

Yeah, the answer to that question is both. There are certainly some small things that could be done to make it more difficult to access, but it's very complex and very difficult to try and deal with these issues. You've seen buildings who might start putting air conditioner units on top of the building, or they might build a cage around them. That's certainly helpful. Other air conditioners have moved from copper to a less valuable metal in the condensing coils. Again, you have to communicate that to a thief. The thief has to believe you, or they might just steal it anyway because they're not going to open it to check first.

The answer is there probably are some fairly simple things that could be done on one hand. On the other end of the spectrum, it's actually quite challenging to really try and prevent the variety of different forms of theft that are going on.

Yeah. I assume a manufacturer could come out and say, “Oh, if we do this, it makes it harder for someone to steal.” Then they just figure out a different way to steal it, but now all your customers are paying 10% more.

Right, yeah. There's always a cost-benefit reward issue here. There's probably some things that could be done that are very low cost. There are some things that could be done that are very high cost. There are some things that are in between that just make sense. Especially if you're in a place where you're repeatedly having things stolen, there are solutions, specifically for electrical utility poles and things like that.

There's a company called In Metal Theft that makes an up-armored door to see the access panel where they would open it. Sometimes those things just pop off or screw off, or these are lock-in keys so that the thief can't really get in there and yank the cable out. Especially in a situation in California, if you have an area that's getting hit over and over again or at a high risk, you can design and put things in place in areas where they're likely to be stolen, and thereby reduce your risk in those ways.

Yeah. Put equipment where you need a cherry picker, or your access ports are requiring a cherry picker or a ladder to get to as opposed to, “Let me just sit down on the ground and open this thing up.”

Correct. Yeah, that's exactly right.

We'll transition over to package theft because I was going to ask a question about cameras and copper theft, and I don't know that it makes sense. Package theft, to me, is just a really weird crime. Does this have long origins, or is this thanks to Amazon?

I think that the increase in home delivery has just skyrocketed. The value of packages and things contained in them has also gone up. -Ben Stickle Share on XI think it's a fairly new concept now. It's not to say that it didn't happen years ago, but I think it's a fairly new thing for mainly two reasons. I think that the increase in home delivery has just skyrocketed. The value of packages and things contained in them has also gone up. I also think to some degree, that the social media awareness of this—listen, this is low-skill, potentially high reward.

You mentioned earlier, the risk of you're not going inside someone's house, you don't have to have any skills like you would to cut off a catalytic converter. You don't have to know where to take it to a scrap yard. Literally, you walk by a house, you take a package, and you walk away. It is the easiest crime that there probably is. I think the ease of it, the high volume of packages, and the increased price has just led to this massive amount of package theft.

Literally, you walk by a house, you take a package, and you walk away. It is the easiest crime that there probably is. I think the ease of it, the high volume of packages, and the increased price has just led to this massive amount… Share on XI like to say this. I think it's probably true; there's not great data. This may be the most common crime in America at this point. Potentially, more people have been victims of this than probably almost any other category of crime because burglary is still fairly rare, if you will. Robberies are very rare, thankfully. Package theft, I bet a majority of your listeners have had a package stolen, so it's a real issue.

I think I've been fortunate enough, particularly probably because I work from home, that when a package shows up, I'm at the door and grab it before someone else can grab it.

Yeah. You would think that would be the case. I started doing this research right before Covid. During Covid, we saw an increase of this, and that's what everyone said, “We're all at home.” I said, “Wait a second. We're all at home, but we're busy.” I can see my front porch in my office, but if I'm busy like I am right now and a package is delivered, I might forget because that routine, if I arrive home, I go outside, get the package, check the mail.

My routine's off, so it's entirely possible that even when we're home, unless you're diligent like you are, we may leave a package even for longer on the porch than if we were coming in and out on a regular basis. It really has a lot to do with our routine activities and the behavior that we have on a daily basis.

Are there particular patterns to when packages are stolen? Are they following the drivers around or waiting till they go around the corner? Are they waiting till the middle of the night, or is it just totally random, they drive through the neighborhood, jump out, and go grab a package?

There are certainly patterns that seem very organized, where a thief knows when you're going to get your phone delivered to your house, gets updates by spoofing digital numbers and by looking at tracking numbers. -Ben Stickle Share on XI'm going to say again, yes to all of that. This is a very nuanced, very unique crime. There are certainly patterns that seem very organized, where a thief knows when you're going to get your phone delivered to your house, gets updates by spoofing digital numbers and by looking at tracking numbers. As soon as the delivery person drops it off, they walk up and take it before you can open your door. Very sophisticated, highly organized.

At the other end of the spectrum is maybe the young high school kid who's walking home from class and goes, “Oh, those look like a pair of Nikes. I'm just going to take those.” It completely goes the spectrum. I've certainly seen people who are following delivery drivers. They've been caught on video. I've seen people who are dressing like delivery personnel.

I've certainly seen people who are following delivery drivers. They've been caught on video. I've seen people who are dressing like delivery personnel. -Ben Stickle Share on XI've certainly seen people who are following delivery drivers. They've been caught on video. I've seen people who are dressing like delivery personnel. -Ben Stickle

Some of the videos I looked at early on, someone would come up with a clipboard and a fake or an empty box. They'd act like they were knocking on the door. They'd look around, they'd take the package, they'd leave the fake box, and they'd run away. It really is absolutely everything on the spectrum you can think of.

I'll just add this one because it's interesting. I did a survey recently of people who stole packages—believe it or not, people answer these surveys online. There was more than a couple who told me that they do it for revenge. In particular, for not tipping delivery personnel. Quite a few people say, “I didn't get my tips, so I took their package.” Another one said, “My neighbor's kids are loud, so I stole their package.” It really runs the gamut, if you will, of everything from highly organized, highly structured, very skilled to do that technically to literally, “I'm angry at you, so I'm going to take your package.”

I did a survey recently of people who stole packages—believe it or not, people answer these surveys online. There was more than a couple who told me that they do it for revenge. In particular, for not tipping delivery personnel.… Share on XI've definitely observed odd patterns in my neighborhood. During Covid, my wife and I would do our walks a couple of times a day. There's a house in the neighborhood that we always called the Amazon house because there was always a stack of packages outside their front door. Most people are pretty good about within an hour, a couple hours, or within a day, their package, they would bring it in. This house, the boxes would sit outside for a week before they would disappear. We always thought it was unusual, like, “You stole my neighbor's package, but here are all these boxes by the front door. They've been there for two weeks and you haven't touched those ones.” Do you think it's bait?

It really runs the gamut, if you will, of everything from highly organized, highly structured, very skilled to do that technically to literally, “I'm angry at you, so I'm going to take your package.” -Ben Stickle Share on XThe constant question I get is, have I ever done any bait packages? The answer is no, I've not. I think because that's what people see online, this would tell me for example, if you have a neighborhood and you've had packages stolen but not from that house, that would lead me, putting my police hat back on, to say, it's probably someone who lives in your neighborhood who goes, “If there are too many packages being left there for that to be random, I better not because it could be a bait house.” That would be my initial reaction. It could be wrong. Maybe they just think it's too good of a thing. It can't be that good and just pass it up either. It's hard to say why they would not stop there.

Anecdotally, I would think that things like Ring doorbells and cameras in the homes would prevent or reduce package theft. Does it actually do that?

The problem is we have more cameras now than we ever had in our entire history of anything, and it doesn't seem to be having a lot of effect. -Ben Stickle Share on XThat seems to be the way that it's sold to us, that cameras are going to prevent things. The problem is we have more cameras now than we ever had in our entire history of anything, and it doesn't seem to be having a lot of effect. The first time I ever researched package theft, I had a brilliant undergraduate student named Melody Hicks come in my office. She had a relative had a package stolen. We were discussing this and I said, “Let's look this up.” We come to find out that no one had ever researched this topic. It was a new thing; it was around 2019.

I like to say I did what any self-respecting criminologist did when they can't find an answer to a question: I watched YouTube videos. I basically started searching in 2019. We found about 70 YouTube videos of the crime in action, if you will, and started evaluating what was going on during these videos. It's a slightly biased sample because I don't include it if it wasn't caught on camera. However, none of the thieves seemed to care. I was really shocked because we wanted to code for, did they try and disguise their appearance? Something like less than 5% actually did.

Many times a thief would walk up to a house, they'd get close enough to the porch, they'd see a doorbell camera, and you see them because they'd look at it, they'd look at the box, they look at the camera, they pick the box up, and walk away. Only a handful of times that anyone try to hide their face, put a hat on real low. I think the reality is people are fairly intuitive and know that the odds of there being a camera, then the odds that it's going to be recorded, then the odds that you're going to give it to the police, that the police can figure out who you are on the camera, if it's of sufficient quality, all those things together, it just isn't going to happen.

Thus far, I don't have any hard data on this, I don't think cameras are really going to be the help in all this other than maybe identifying who did it or knowing what happened to it, so you can verify it was a person and it wasn't the neighbor's dog that drug it off into the bushes, and occasionally provide a humorous video of someone who falls and breaks their leg or something. I don't see a lot of utility in the prevention on the camera side.

Yeah. One of my neighbors, she lives at the end of the alley. She has a Ring doorbell. The neighbor across the alley has a doorbell. I'm up partway down the alley, and I've got cameras on my house. Between the three houses, we got the license plate of the vehicle pulling in. The guy who stole the package looked at everybody's camera, straight at the camera. Sure, Ring doorbell cameras aren't that good, but I had a 4K camera. He looks right at the camera. They don't run, they just walked, got back in the car, drove off, and stole $20 of toilet paper or something. It was something that was totally worthless in that sense. It's in the middle of the day.

One of the important things that we need to remember—we talked about how to prevent crime—is there are three things. I've adopted this from an organization called the Loss Prevention Research Council that really specializes in these types of things. They have a saying, they call it see, get, and fear. A criminal or a would-be thief has to see the deterrence, has to get it as in they have to understand it, and they have to fear that there's a consequence attached to it. I think cameras are so common and ubiquitous in our society that they see it, they get that it's a camera, but they don't fear it because they know that this isn't really going to catch me. No one's really going to care.

Let's be honest, let's just take it a step further because I get lots of phone calls when states say this is now a felony. We can barely keep anybody locked up who's assaulted someone. The idea that we're going to call someone stealing a pack of athletic socks, make it a felony, and they're going to actually spend time in jail, let's be honest with ourselves and our society, it's just not going to happen. The question really becomes then, are there techniques and devices that a criminal would see that they would understand it and they would fear it? I think the answer is yes to some of these in a package theft perspective.

What does the responsible homeowner who doesn't want their toilet paper being stolen do?

Amazon's allowing you to schedule. At least they were allowing you to schedule delivery windows. The goal is to be home and to remove it from the porch as quickly as you can. -Ben Stickle Share on XYeah. There's a couple of free, easy things to do. Amazon's allowing you to schedule. At least they were allowing you to schedule delivery windows. The goal is to be home and to remove it from the porch as quickly as you can. Generally speaking, beyond the highly organized thieves that I talked about earlier, this is a crime of opportunity. The longer a package is there, and in particular in my research, I demonstrated the closer it is to the roadway, the more likely you are to be a theft. That's all about opportunity.

If you can receive it when you get it, that's better. If it can go even inside the mailbox, that's better than sitting on your front porch. If you can have something on your front porch like a plant, a bench, or something where you can hide the package behind it, that's fantastic too. Failing that, you can have it delivered to maybe a neighbor, a family, or a friend who is home. There are other options where you can pick up at lockers or at a local store. Those all tend to be usually free or about free.

If you have a lot of packages delivered and you're at high risk, you can certainly get a home parcel-like locker system. I've had one of these on my porch for years by a company called Adoorn. They make a nice looking box that you can attach to your house, that would receive packages and keeps them safe from those who might steal them. Again, the key here is the would-be thief doesn't see that it's there for the most part. That's really helpful.

If you want to really look at this—again, we go back to our see, our get, and our fear—there’s a company called Ziflow Technology that has a very small device. It's a one-time use GPS tracking system, and it can be attached to the outside of a box in the shipping system. The beauty behind this is once it gets delivered to your address, it arms itself. If it's moved or taken outside of the geofence area before the owner disarms it, it sets off an audible alarm and flashes a light. On the outside of it, it says, “Theft deterrent package. No package theft.”

Again, this is something that an offender would see. They would get it, and they would fear it because there's a risk in it, because they know that not only will it set off an audible alarm, neighbors are going to come out and see me. It'll track them if they run off with it. There is a product that is getting at all three of those things. Not only does it prevent theft, it's helpful to know when your delivery arrives at your door, how far away it is.

The front porch is now the center of commerce for pretty much everything. -Ben Stickle Share on XThere are solutions coming online that will really change this. Ultimately, Chris, I tell people that we really have to rethink the front porch. The front porch is now the center of commerce for pretty much everything. We still go to stores, but not as much as we used to, but we still build porches and have porches the same way we have for a long time. Just like we used to have a coal shoot back when we had coal furnaces in our basements and the coal truck would come and deliver it to our basement, around that time we had little cutouts in our walls so we could exchange milk bottles when the milkman would come.

We’ve got to rethink our house. How are we building these things to receive packages? I don't think that's going to stop anytime soon, so we've got to think from the beginning. In the meantime, there's a lot of things that we can do.

We’ve got to rethink our house. How are we building these things to receive packages? -Ben Stickle Share on XWhat would the change to a porch be that would reduce package theft, like an S turn to get to the front door or space that is just obscured from the street?

Yeah. That's certainly an easy thing to do. Like I said, you can do that today. I've seen videos. I've not done this myself because I said I had the lockable box in my front porch. Even just an empty box, not a cardboard box but like a decorative box or something like that, even if there's no lid to it, and just on the inside on the front edge, when someone would walk up to deliver a package, it just has an arrow that says, put package here, it keeps it not visible from the street. You can build that in as part of the structure. You can add that later.

I've seen new designs. Again, these are still coming online, where basically there are two doors, not your main door, but there's a side door. From the outside, you can open it up and it's got a small closet, maybe two foot by two foot. On the inside is another door. You can't open both doors at the same time, but it allows the delivery driver to basically deliver inside your house, and then you can come home and open the inside door and get that out. I think we're seeing some designs with those types of concepts coming online, which should be very helpful as well.

I guess the Amazon-have-access-to-your-garage-door plan didn't actually pan out well for that.

Yeah. I remember when that was being advertised. I wasn't sure that would work. I know I would not have allowed it. I didn't want that, nor do I want someone opening my front door and putting a package inside either. I've wondered the liability when the dog escapes, you don't lock it back, or something.

There was a company, I don't know if it's still in existence, called Frame. They had a design where an Amazon or someone could pull up to your car, and it would allow them to open the trunk. They could put a package in your trunk. I actually thought that was a pretty good idea because I would let someone get in my trunk most days, especially the concept was you could deliver it wherever you're at. If I'm at work in the parking lot, by the time I get home, the packages were delivered at work and I can go along my business. There are lots of creative ways. It's just getting that switch from what we're used to to what needs to occur to make us safe.

As we start to wrap up here, any general philosophies on how to reduce the opportunistic portion of opportunistic crimes? We talked about if they can't see it, we can hide things. What other things can we do to make opportunistic crimes less likely in our lives?

That's a really good question. I know you cover a wide variety of topics on this podcast. Let me give you a quick, broad answer to that. I generally refer to myself as what's called an environmental criminology. The concept there is it's not really about pollution, which is what it might sound like. It's more about, how do we structure primarily the built environment, cars, houses, buildings, to be less opportunistic for crime? I would rather prevent a crime than have to worry about arresting someone and dealing with that whole process. I'd rather just not have the opportunity.

The question to your point is, how do we do that? One thing that I've learned, both from studying and from actually application, is that when we're looking at crime prevention, it needs to be very specific. The question of can we reduce opportunity, the question is absolutely, but opportunity for what?

I'll give you a quick headway. I have a paper coming out here in another month or so. We looked at metal theft in the city of Louisville, Kentucky. What we found is across five different types of metal theft, like the wires you were talking about as opposed to air conditioners, as opposed to sewer grates, as opposed to catalytic converters, et cetera, when those thefts occurred and where those thefts occurred very drastically.

If we just look at even metal theft or package theft and say, “What can we do broadly,” we're going to probably miss the mark. What we really want to do is say, “OK, package theft in a residential neighborhood, where the streets are 50 feet from the home with this much foot traffic, what should we do as opposed to how do we reduce opportunity in a high-rise apartment complex?” The goal that I always want people to think about is be very specific in your crime prevention and opportunity-reduction strategies. That's where you get the success.

That's why it's really important to have folks who will research these things, think deeply about them as I've tried to do, and then be very specific about how we prevent that. Some things are going to be more universal than other things. There's no doubt about that. Locks are generally good on most homes, but locks only keep your neighbors out. I used to say that when I was a cop, and I'll still say it today. Being very specific about what you're doing and where is really the key to reducing the opportunity.

Being very specific about what you're doing and where is really the key to reducing the opportunity. -Ben Stickle Share on XIt's very issue specific.

Correct. Absolutely. That's going to change too. If you're in California, that might be different. I'm in Tennessee and it might be different from Vermont. It's issue, it's location, it's type of crime. It's very specific and driven to the environment in which it's happening.

I like it. I like that response and I don't like that response. I don't like it because I can't do it. It requires me to think more about what are my risks and how do I reduce each of the specific risks, as opposed to just put up a camera because that will fix everything.

Right. Those things rarely do. I guess that's the message I try and get across. A one-size-fits-all for a broad category crime isn't going to really move the needle. Again, if you don't leave your bicycle laying in the front yard, it's less likely to get stolen. That still doesn't answer the question of, “What if it's behind my house and there's an alley, and people can walk up that and see it?”

Every type of crime, theft, or even personal violence, your risk for being assaulted when you're at a bar is drastically different than when you're at a sports game, which is still wildly different than when if you're at the public library. Understanding the risk specific to when and where you're at and what the risks are and then applying behavioral processes to put yourself in a more safe space or a more safe environment is absolutely key to everything we do. We don't want people walking around thinking, “Well, I'm going to be assaulted,” when there's much less likely for that as opposed to a theft, for example. Understanding risk, understanding where you're at, who you're around, how you can protect yourself, those are absolutely essential.

Understanding risk, understanding where you're at, who you're around, how you can protect yourself, those are absolutely essential. -Ben Stickle Share on XI suppose a lot of police departments probably publish relative crime statistics about certain types of crimes. If we're seeing a trend increasing in this area, then you can go, “OK, that's what I need to be focusing on preventing it. How do I prevent that specific crime from happening to me or my family?”

Yeah, you're correct. A lot of departments are moving to publishing their information online, especially. I have my students do this just a couple of weeks ago. They looked at an online portal for crime statistics and where they lived. It's like a week delayed, but it gives them an idea. Then I had them compare that with their hometown or a friend who lives somewhere else and look at the risks that vary so they can identify what that is.

I will just add, the most horrible thing you can do is watch the news because they're just going to try and push everything they can that is an alarmist and you're worried about without revealing the true reality. You could watch the news and be more worried about a mass shooting, which are still very rare, and forget that your package was stolen while you're watching the news and worried about getting involved in a mass shooting. Understanding your risk and what's at stake is very important.

Are there any emerging opportunistic crimes that you're like, “Oh, I think this is going to be the next porch pirate?”

Yes. I have branded myself as doing emergent crimes. Not necessarily new—metal theft’s been going on forever, for example—but new as in popular. Some of the other areas that I've looked at is what happens to crime in the sharing economy. We are fast approaching. This is getting well beyond an Uber and an Airbnb, although they're included. You can rent tools from each other. Students have book exchanges. You can lease your prom dress to somebody else. There are endless opportunities.

The internet has removed that barrier. We're able to find people to trade things with. You can rent your backyard pool to somebody else. That brings with it some opportunities for crime. At the same token, I think it actually brings a lot of protections. We used to be really worried, and I still see people worried, “Oh, we get in cars with strangers with Uber.” Yes and no, because there's a guardian—that would be the company Uber—who knows who I am more than likely, the driver almost certainly, and they're monitoring our behavior.

Years ago in a taxi, you didn't know who your driver was. You didn't know if it was a real taxi, probably. Maybe they had the sticker somewhere. Digitally now, we have what I call digital guardians who are able to oversee and make sure we're doing something. Same idea with a tool. By borrowing neighbors' tools through an app, I've signed a contract saying, “I'll give it back on this date,” as opposed to I borrow a hammer from a neighbor and I just never bring it back. Then there are all kinds of issues about was it a criminal offense, is it a contract violation? The sharing economy is going to be huge. It's going to change everything about how we interact with people, and it's going to totally change crime.

The sharing economy is going to be huge. It's going to change everything about how we interact with people, and it's going to totally change crime. -Ben Stickle Share on XAnother area that I've looked at that I recently published a paper on is pet theft. This is a growing issue, especially in California. People are stealing dogs, they're holding them for ransom, and they're doing all these types of things. I have another paper I'm working on, also California dataset. Beehive theft is apparently an issue. Metal has tremendous impact because if the bees don't pollinate the almonds, then you don't have an almond crop. There are all types of these emergent crimes that are coming online.

The challenge is we don't keep good records of them, so we don't know how they're happening. Most of these don't involve calling the police. They're new and emerging. I like solving hard problems, so I find myself attracted to those types of crimes.

I like it. If people want to read your research as it gets published, where can they find that?

I do a decent job of keeping up with my website. That's just my name, benstickle.com. You can visit that and a lot of my stuff is on there. There are ways to contact me if you'd like to chat about something. I try to give links to free articles. You'll see that I try very hard to publish a scholarly paper, and then I also publish something that's free to access and free to read. Most of the links, if you go there, benstickle.com, you should be able to find most of my work.

Great. Ben, thank you so much for coming on the podcast today.

This has been a pleasure. Thank you, Chris.